|

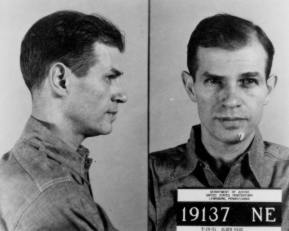

GPS, aged 20; just discharged from USAF in 1945./Dresden - before and after the bombing(Wikipedia)

Dash dot dot dash dash . . .crouched in the radio cabin, he can hear the sounds of the explosions, planes packed with high explosive being shot out of the sky. Up the little steel ladder to the gun dome, in the top of the Flying Fortress.

All around him the sky is full of magnificent dreadful fireworks, tracer fire from enemy fighters, screaming towards the dark fleet of bombers; anti-aircraft shells arcing up from the ground in deadly, beautiful patterns.

All around him the sky is full of debris and flak, hitting the fuselage; planes spinning in slow motion towards the ground, with bits of boys from Iowa, sons from Chicago, young men from farms and colleges spread across a land most had never seen, and none would ever walk on.

As he sees the flames work their way along the body of the plane, he fires off one more message - one that was sent directly to the base, unheard by the others in the squadron.

Dot dash dot dot dash . . .struggling to close down, get his kit, start to stumble towards the hatch. As the plane starts to tilt in it’s final descent, and the smoke fills the fuselage, all he can hear is the shouting and screaming from the crew.

He’s never jumped before, but it’s that, or die with the plane which has started to howl like a dying beast. He’s hauled to the hatch and all he can hear is the officer shouting, and before he can think, he’s pitched through the door, floating down, down to the distant Earth.

He knows that he has been told not to pull the 'chute-cord until the second cloud layer, and that if he pulls the cord now, the fabric will rip, the Germans below will see him floating, he will die. It’s too soon, and he can see other airmen tumbling out, pulling the strings, their chutes torn away.

And down below are men who will kill him if they can.

This he thinks, is it.

The end of the story of the boy from Detroit,

He blacks out.

Consciousness and the Earth is spinning towards him, close enough to see the shapes of things taking form. The drill kicks in, he pulls the cord, and like a brake, the silk parasol spreads out above his head, and the speed and the spinning become a slow motion film, in which he sees the garden, and in the garden a tree, which rushes towards him and catches him in its outspread arms.

Like so many of the young men from across the Atlantic who had joined up to fight thousands of miles from home, that George Solomos never really returned.

His exile was as much a spiritual one, as a physical one. though. . .

For as he left the burning plane and floated in freefall into Occupied France, he was starting a journey, which would make it impossible to return to the life he had left back in Detroit, USA.

***

In a small flat in South London, a figure is moving from screen to screen. Computers flicker in the background and the sound of Al-Jazeera’s hourly news comes from the kitchen at the other end of the corridor.

The phone rings and we hear the words “Hi, George Solomos here . . is that the Veterans organisation? I need you to sort a coupla things out for me”.

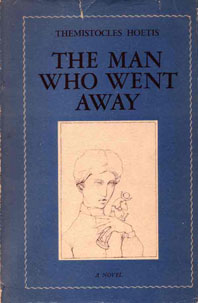

Themistocles Hoetis, also known as George Solomos - or to use the title of his first novel, published in 1952 ‘The Man Who Went Away’ - has come a long way from the Detroit of the 1920’s.

|

|

| Front Cover; The Man Who Went Away, published 1952. George drew the picture above. |

Back Cover; This picture of the young GPS was on the back jacket. |

GPS's first novel, published in 1952 in New York by Pellegrini & Cudahy. Options for the UK were taken by Victor Gollancz.

Detroit was a pleasant slow moving French American city, with markets selling produce from the outlying farms; theatres, restaurants and bars like any medium-sized European city of the time; and a city like every other in the world, where legs and horses were still the mode of travel, and in which the Ford Motor Company was just another small engineering concern.

‘By the time I left for Europe the whole place was being covered in concrete and tarmac. The boulevards were disappearing, and that man Ford was taking over the city’

His father was a Greek who had brought the love of his country with him, and started a general food store, selling quality and general food for Detroit’s diverse communities; from fresh prepared meats, cheese and olive oil to chilli dogs for the local factory workers; and Mediterranean produce to the many other migrants from that part of the world.

Already George had started realising that there was a world outside the city, through the books he voraciously read as a boy - from Freud to the great Russian and French writers of the nineteenth century. He was so keen on French culture that he took classes to learn as much of the language as he could – how little did he realise then that this would later save his life. He was also a media-junkie, telling how he would send off for ‘free issues’ of any publication that had a subscription offer; as well as reading his father’s daily news, the Detroit Free Press, a paper started by Quakers in the city many years before and source of much discussion in his household about the climate of current international affairs.

George’s education was supplemented by the films that he saw when he had to accompany his teenage sister (later the secretary of mobster union boss, James Riddle "Jimmy" Hoffa), who would drop him off in one of the many cinemas before meeting her admirers.

Later, she might leave George at Club Sudan to take in the rhythm & blues and jazz while she enjoyed the night life of Detroit.

He left the US on a troopship in 1944 at the age of seventeen when he forged his papers, with his father’s agreement - in the way of the Spartans - to join his squadron based in Suffolk.

He knew perhaps a little more about Europe than his fellows, although the distance for most of them from the ‘old’ continent was a couple of generations at the most.

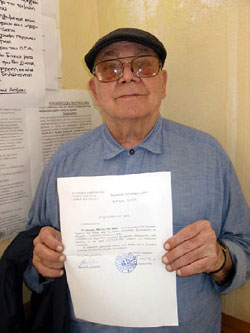

|

GPS in 1991 with his father's birth certificate |

George's family had never forgotten their roots in Sparta; they had left the Kingdom of Mistra, last refuge of the Byzantines, after the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople and ended up in Venice.

Ironically, the pillage of the Eastern Empire by the first Western Crusaders(as well as the Bubonic Plague) - weakened it so much that it could not resist the Turks - and resulted in the 'Enlightenment' of the West and the triumph of (classical) rationalism over the 'superstition' of medieval Rome. The obverse side of the pillaging of the Ancient Eastern Empire - a trend the West continued forthwith and continues to this day - actually led to the great art of the Rennaissance and the inspiration for 'artists' , philosophers and humanists such as Rousseau.

Along with the other great City States of the Italian peninsula, such as Florence, Venice took in the refugees from these places - the nobles, learned men, soldiers - and used their skills and what riches they brought with them to become the beacons of light in Western Europe at the time.

However, the Byzantine refugees never forgot their history, across the Mediterranean Sea; and the century before George's birth, one of his more recent ancestors had been Dionýsios Solomós , who wrote the Greek National anthem and is still regarded as Greece's National poet.

On George's first visit to Greece after the War, he witnessed the wasteland that the country had become; first ruined by the German and Italian fascist armies, and then by the Greek Civil War ; in which the 'Allies' had already turned their attention to the Cold War borders, and were aiding the Greek 'Nationalists' against the Communist partisans who had done so much to free the country from the Nazis.

Like the A-bomb, this seemed preferable to the US at the time, than risking the 'spread' or reinforcement of socialism, communism or 'Soviet' influence in their future 'markets' of Europe or South-East Asia.

But this strategy also made George, and many like him, question the values of the political masters in the USA, and the 'values' that they had so courageously offered to fight and die for - he had no dilemnas about what he had been fighting against.

Perhaps this is one of the enduring themes of George's work; the role of arts and artists to question the status quo, the received wisdoms, and to sometimes shed a little light on the way through the darkness we are kept in.

***************************

Wartime London was a revelation, the capital’s underground bars and drinking haunts for the ‘spivs’ and gangsters suddenly blossoming with the Yankee servicemen, their jazz music and their money; as well as their irreverence and disdain for the British class system and licensing laws.

Deserters, black marketers, musicians and ‘ladies of the night’ found fellow desperadoes amongst the airmen, especially the Yankees, whose every leave might be the last, and no pay – cheque was worth saving.

He tells how he was exposed to the full-scale devestation being wreaked on wartime Britain and recalls a young woman he had dated. The third time he had gone to meet her at her home in Whitechapel, he was shocked to see that her street was now a ruin, with signs saying ‘No longer inhabited’.

‘The Americans were your friends’ - he says now - ‘your allies, and they just stood back and watched this country being bombed into poverty. And after the War, who did they give the money to ? The Germans and the Japanese, because they wanted some good anti-communists facing the East; and they suspected Atlee and the British with their socialist ideas like the NHS . . and of course, they wanted to steal the rest of your empire . . .they were the biggest imperialists of them all . . . ’

George flew eleven bombing runs over German cities from his base near Ipswich.

One out of every two planes would be taken out on some runs, where up to a thousand bombers would fill the sky; and the heavens and earth would be turned into a hell of fire and screaming metal.

He was the radio-operator, keeping the crew in touch with their squadron and the base. Once radio silence was called by the pilot, as they crossed into enemy airspace, George would be required to shin up the ladder into the small dome on the top of the plane’s fuselage, and operate the machine gun, looking back beyond the tailplane to watch out for, and shoot down, any German fighters that were coming at them from behind.

Like most who took part in the destruction of the German cities, George has had to deal with the memories in his own way; and he chose the path of creativity, rather than a guilt leading to self-destruction.

There was little question, by that time of the war that Hitler was determined to fight to the bitter end if needs be, and that the Nazi regime was prepared to inflict inhuman suffering on any it perceived as their enemy.

Years later in an interview on Cuban TV(in 2001) he was introduced as someone who had been fighting Nazism since he was a young man. He told a German friend pointing to an old bomb-crater in Hamburg “Gee, I could have done that . . ‘

But like so many of his generation who returned home, to find they had been so changed that they did not recognise their own country – which itself had begun to change in the way it viewed both itself and the outside world – George Solomos became a different person the moment he pulled the rip-cord and started floating down, ending feet up, head down, in an apple tree, in the garden of a French woman and her granddaughter who fed him and hid his parachute. Told to get in the cellar, beneath the kitchen table, he could soon hear the sounds of German soldiers conducting a quick search above him, and then they were gone. Transferred to a hideout in the fields, he briefly met a Basque-American, who was another survivor of his crew; he was there for a week, then was hurried across the countryside and given a fake passport. He was then hidden in the basement library of Marie Cassatt's Chateau, safe and secret beneath the flagstones.

Marie Cassatt's Chateau and her picture of Mother and Child

He stayed there, for a month, and the only person he saw most days would be the daughter of the caretaker of the house, who would bring him food, and fruit, and cigarettes.

But George had discovered something in hiding, which suddenly became more overwhelming than the loneliness, or the fear of imminent capture.

The cellar where he was hidden was full of books, great histories and first edition novels; kept away from the Nazis, whose fondness for appropriating ‘Kulture’ had become well- known by countries from France through to Russia.

George worked his way through philosophy, history and fiction, learning more about his homeland from reading Zarate’s ‘Conquest of Peru’ than he had in all of his history lessons in Detroit.

Not only that, but George had not finished his exams, because as a dyslexic – a virtually unrecognised condition in the 1930’s - he had little opportunity to go to college.

Now that books were his only window to the world outside, he began to read voraciously again.

It’s 1950 and George Solomos is sitting outside Les Deux Maggots, one of the famous Bohemian cafés on Paris’ Left Bank . Drinking coffee inside is Jean Paul Satre, the philosopher; and at George’s table are a couple of aspiring poets from the Sorbonne.

Cafe de Flore, Paris at the end of the War

They have come to meet George because he is the publisher of one of the Left Bank’s most famous magazines, a compendium of previously unpublished writing called Zero.

He has started the magazine up with his GI’s pension, and a bit of patronage from the rich Americans who always hover around ‘scenes’ in old Europe; in the years before US culture became so confident, and Hollywood aesthetics so dominant across the globe.

George had survived the War by being smuggled across France to Spain by the French Resistance, a melting-pot of Communists, socialists and peasant anarchists from the rural communes - as well as it’s share of ‘patriotic’ gangsters, and humanists appalled by the inhumane excesses of Nazism and the Vichy Regime.

Only one other member of his crew survived the jump that night, he learnt later.

George was to be smuggled across France in stages - once pretending to be the deaf-mute son of a French couple - in an operation that was estimated to have cost the lives of considerable – possibly 12 - Resistance members, as the Germans knew he existed, and were always just one step behind.

It is remarkable that this was happening to a youth who only shaved for the first time just before he reached the Spanish border.

He crossed under a bridge with a fellow GI escapee as Germans searched everyone crossing above into ‘neutral’ Spain.

He, and many other were then returned to the US, where constant debriefings, along with the ‘truth drug’ Sodium Pentathol began to alert them to the terrible truth. His medical records, which he only obtained from the military in recent years called him ‘unco-operative’ and ‘resistant to treatment’.

|

GPS, age19 at the AAF hospital, 1944 |

‘The closer contact you had with the Resistance, the more insistent they were’ said George.

‘They were really interested in the Resistance members who had been Communists, and those guys had been the backbone of the fight against the Nazis.’

It was only when George and his friends returned to France after the War that their worst fears were confirmed.

Many of the Communists who had helped them escape had been the final victims of the retreating Nazis, after evading capture for six long years.

And the ones who the Nazis did not catch were often taken for “interrogation’ by the incoming Allied (generally US troops).

‘Even before the war had ended, the people back home had started talking about going for the Russians” says George.

‘The whole atmosphere was different by the end of the war. Detroit had become Motor City.

In fact, it seemed like however far I went to escape it, soon the whole world was tarmacced over. And that man, Ford, was making money out of slave-labour factories in Germany producing his motor-cars, and publishing his anti-semitic trash, whilst my friends were dying over Europe.’

He briefly saw his family, and that was the last time he saw his father before he died. George later regretted not having the opportunity to reconcile his post - war self with his father, who had always encouraged his freedom and independent spirit.

As soon as the War was over he did his year’s college at Detroit State University, and he headed to France, clutching a pass to the Sorbonne which he never actually took up.

There, from his apartment on the Left Bank, on not much more than his GI’s pension, George began publishing Zero; taking the same meticulous care with the layout and content that he has with every one of his subsequent publications.

Apart from its list of contributors, which reads like a “Who’s Who” of the literati of the fifties, George’s most important contribution to the world of publishing at this time was his fostering of the career of a young black writer who had ended up in Paris.

George found a patron in Paris almost immediately, a man called John Godwin, who was related to the impressionist painter Maurice Cassatt (in whose chateau he had been hidden in at the start of his escape through France). Godwin was the scion of a wealthy family that had earnt its fortune from the Pennsylvania State Railroad Co., and who had been tutoured by Gurdjieff. He was already known in the American art world for a radical theatre group he had set up in West Hollywood, and from 1946-7, he introduced George to the writers and thinkers on the Left Bank, including a young black American called James Baldwin.

Richard Wright (1908-1960) & James Baldwin (Born August 2, 1924 in Harlem, NY, died December 1 1987, St. Paul-de-Vence, France)

As a friend and publisher of the black American Marxist novelist Richard Wright - perhaps the first great, black American author to reach an international audience, and an American political exile himself - George was well aware of the barriers preventing expression of a truly black American identity in his homeland. Before the war was even fading from memory, those African-American GI's found that they were returning to the same master-slave relationship with the WASP nation they had so honourably fought for, and the Civil Rights movement started to pick up momentum. It was during this period that George helped James Baldwin on his path to becoming the first universally well-known black dramatist of modern times.

He published some of the first work of Baldwin; and later ,with his wife Giska, took care of the gifted, complex, but tragically self-destructive writer, whose alcohol addiction plagued his adult life.

George returned to the US to see if the political mood had improved enough for him to publish freely, and to take back some of the philosophy of the Left Bank.

He attracted the attention of Professor Basillicus, at Wayne State University, and put a collection of William Blake's poems together for the College Press. This won the First Prize from the Poetry Society of America, and the professor gave him the chance to publish a second. George’s choice of the Committee of 100’s report on Nuclear Policy (one of the authors was Bertrand Russell and George had jacket quotes from Eleanor Roosevelt) was eventually stopped at the last stage before publication.

The University's main sponsors were GM Motors, who threatened to withdraw funding if publication went ahead.

He realised that Europe might present more opportunity for ‘free-thinking’, and it did not take long for his instincts to be confirmed. In 1953, George received a Rockerfeller Grant to live and write in Mexico City, where he completed his still unpublished book Thermopylae ; the first writing in which he had attempted to wrestle with the demons of the war that had never left him and the problems of the spirit in rigid societies.

George had already attracted adverse attention from the FBI by 1954, when he was visited by a couple of their thugs at his apartment after his time in Mexico City. They were probably keen to see if they could tap any information from him about the political inclinations of his friends, in a time of anti-communist paranoia, stoked up to a large degree by the strange Edgar Hoover, as well as the right-wing US Establishment during the McCarthy period (and since).

‘You people wouldn’t pay me as well as the Russians !‘, he chortled, shutting the door in their face.

When he obtained his (heavily censored) FBI file 30 years later, he was pleased to note that he he had been listed as a 'known associate of homosexuals and communists'.

George had a wide social circle at this time; from people like filmaker and poet George Morse, to the dilletante upper-class Yankee liberals like the Guggenheims.

He tells how the Korean War had just started and he heard that service personnel from WWII who were young enough to serve, like himself, would be drafted within twenty-four hours.

Aside from the fact that the two wars were against completely different sorts of enemies, George had by now decided that he could no longer trust the political masters of the USA. And after his experiences the last time around, George felt he had had enough of warfare.

He went around to his patrons to ask for a ticket out, and Peggy Guggenheim famed for her art collection and relationships with the avant-garde of pre-War Paris, wrote him a cheque for $250.

‘I don’t want a damn cheque, I need cash!’ said George.

She looked at him, and then pointed to the signature on the cheque.

‘They’ll give you cash’ she said ‘You won’t have to wait . . .’

‘I went straight to the bank . . . they handed it over straight away, and I was out of there . . .’ says George.

*** In 1956 Zero Press soon started publishing books, including 'Brothers and Sisters' by Ivy Compton-Burnett and 'A Thirsty Evil' by Gore Vidal.

During his period in New York, he also tried to enlist the famed - and framed - diplomat, Alger Hiss, whom he met through James Baldwin's publisher, to be his business manager; but in the ‘Land of the Free’, was made aware that if he did so, he would be excluded completely from the American world of letters. This reinforced George's view that the US was run by an elite for whom true freedom of thought and opininion was something to be afraid of - a perception that he feels is as true now as it was then.

This world may be built by brawn; by muscle, sweat, blood and tears - the same force used to tear it all down, epoch after epoch. But this force is motivated by inspiration and imagination; the wish to create monuments to memory or build newer, better worlds. That is why freethinkers - intellectuals and philosophers, poets and writers - strike fear into the hearts of those who control the wealth of this society. There is only one thing more powerful than money, and that is an idea; a thought that can project itself from the mind of one into another. An idea is like a virus, it can pass from person to person without a trace; and even those who do not succumb to its persuasion can pass it on to others. Its transmission through one mind to another can lead to mutation and improvement until it becomes stronger; until it can survive the death of the original host, immortal in its transendence of time, place, circumstance.

People like George, Alger Hiss, Richard Wright, Mumia, Lennon - they all scared the shit out of the rats sitting at the top of this particular dungheap; because they dared to question the puppet-masters, showed people the strings stretching from their backs and gave them an understanding of how they could cut the strings and begin to dance freely; find their own ways to rip up the masters' blueprints and profit sheets; to build a new world based on ideas and not the fools gold of dollars and sterling.

|

Alger Hiss in Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary

(Photos courtesy of the Federal Bureau of Prisons) |

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alger_Hiss

http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/USAhiss.htm

http://www.webcom.com/~lpease/collections/disputes/hiss.htm

George became a ‘mentor’ to various artists, like George Morse, and Irving Thalberg Jnr (1930-87), the son of the great, doomed Hollywood producer who died at the age of 39.

Thalberg Jnr was inspired by George’s poetry and his pursuit of the artistic ethos; and later turned his back completely on his family’s showbiz tradition and became a noted professor of philosophy.

George also was one of the first wave of American ‘exiles’ to make their way to the exotic ports and hinterland of Casablanca and Morocco; carving out a path followed soon after by the “beatniks” like Allen Ginsberg and Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones.

|

|

Paul and Jane Bowles, 1949. pic. by Cecil Beaton |

A. Benveniste & T. Hoetis in Tangier 1950 |

He made a special journey to see novelist and composer Paul Bowles and his wife, the writer Jane Bowles, who had lived – by middle class American standards at least – a remarkably free and bohemian life.

An article in the fashion magazine Flair published with a transparent cover and aimed at the New York literati, run by the Conde Naste heiress Fleur Cowles (he was a good friend of Joanne Conde, who loved jazz as much as he did) called George one of "an apprentice Yankee Balzac - and a be-bop hipster perched on a cliff outside Tangier celebrating the virtues of hashish..", after the author Gore Vidal had visited him in Morrocco and been overwhelmed with the 'atmosphere'.

In 1961-2, George went to Rome,where he first was employed producing the American version of a filmscript about Italians during the War, which was to be narrated by Marlene Dietrich.

|

A still from Echo in the Village - the shepherd boy learning English |

Over the next two years in Italy, George made two films; one a ‘short’ called Echo in the Village which was scored by Bruno Nicolai who went on to soundtrack some of the great ‘spaghetti westerns’; and a feature, Natika, which starred John Drew Barrymore – the louche, morphine – addicted son of the great early Hollywood star, and father of Drew Barrymore.

|

|

John Drew Barrymore |

(June 4, 1932 – November 29, 2004) Photo; from Natika credits |

The half-finished edit for this feature film was taken by the ‘producer’, a man known as Gray Fredriksonn, the son of a US oil family with vast holdings in the Middle East, while George was on a break in Turkey writing his next script.

‘I never saw it again till last year (late 2002)’ says George ‘and this man got his reputation off this film. He touted it round the film festivals and got known as this great left-field film producer, All he did was write me a cheque for $10,000. Next thing I know he’s producing Apocalypse Now’.

This, coupled with the fate of Zero (eventually republished in a special bound - edition by the New York Times in the 1980’s as a book compilation, using copyright loopholes that evaded paying anything to George); as well as the political climate of Fifties America, led him to eventually leave to take up permanent residence in Europe.

He was regarded as a European literary figure; at one point he was invited to Moscow by the Soviet Academy of Poetry, and drove across communist Europe from Italy to get there.

|

Nâzim Hikmet, Moscow 1965 |

In Moscow, he was the house guest for two weeks of the famed Turkish poet Nâzim Hikmet, then in exile in the USSR.

He returned to England in the Sixties , a country he remembered as a bankrupted and ruined society twenty years before; and saw London bursting forth as a fountain of alternative, popular culture.

George's gregarious nature and record as a poet, filmmaker and writer opened the doors to a literary network eager to achieve the vitality of post-war Paris, and he was interviewed for over an hour by Joan Bakewell on a late-night TV arts show.

George continued his publishing in Britain for a while, at one point taking a fragile heroin-addicted poet called David Chapman under his wing ; whose work ‘Withdrawal’ (1964) he published, arranging patronage from Jonathan Guinness and a musical piece inspired by the book from John Stevens' and Evan Parker’s Spontaneous Music Ensemble. The music was performed at the ICA, London. (David Chapman died in 1976 from a drug overdose).

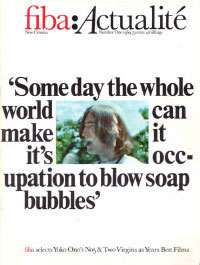

His friends in the UK included literati icons Asa and Penelope (Pip) Benveniste, who were independent publishers of leading poets and writers - including a rich Japanese artist called Yoko Ono who offered to finance George's first film magazine, fiba, just before she started going out with John Lennon.

George met Yoko at a Belgian independent film festival when she was still living with Tony Cox and his daughter, and she immediately recognised a fellow-traveller. She paid £150 for a two page advert in the new magazine, which went on to win

a prize at the Venice Film Festival, and led to a six-month film festival bonanza.

Returning to Britain, George was then introduced by Yoko to John Lennon, who was already beginning to withdraw from the commercial behemoth that the Beatles had become, and was starting to look towards being a political artist, interested in multi-media, and using his fame and wealth to push the boundaries of Sixties culture.

He let George stay in the London flat at Montagne Place, where the corrupt drugs-squad officer had planted cannabis, leading to the conviction which later caused Lennon so much trouble in his attempts to get a Green Card (visa) to stay in the USA.

"God gave us tongues to conceal our thoughts" Brian Epstein

During this time, he also met Brian Epstein - and spent a whole night talking to him at a party a couple of days before his ‘suicide’.

George remains sceptical about Epstein's death, pointing out that the song publishing company (NEMS) owned by the Beatles was a cash-cow desired by certain media-barons at the time, who feared its potential to take over parts of the underfunded 60’s media outlets.

The British Establishment had already started getting suspicious about the ambitions of the ‘pop group’ of ‘beatniks’ and their gay, Jewish, - and very astute, manager.

In 1969 George took Lennon and Yoko Ono’s films on a tour round the US, showing them in up to 50 independent cinemas and colleges from the East to West coast.

He returned to New York, where his car was stolen; very soon he had run out of money and decided to return to Europe.

George heard the news of Lennon’s death a few years later, when he was working in a sorting-office in Philadelphia, and was immediately contacted by the local TV station which wanted to interview him as someone who had known Lennon.

For someone with a studied contempt for the ‘popsicles’ of modern culture, he still retains a deep affection for Lennon, who he believes was assassinated by the US secret state.

As someone who has spent many years trying to retrieve his own military and FBI records, he has no illusions about how dangerous the ‘open democracy’ of the Land of the Free really is in practice.

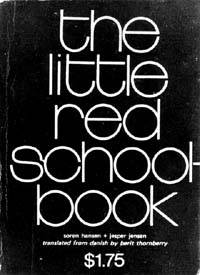

He was in Ireland from 1971-2, working as the film-critic of the Irish Times before being shown out of the Irish Republic by Charles Haughey, after distributing hundreds of copies of the Little Red Schoolbook - to the horror of the Roman Catholic establishment. He had also not made many allies in the cultural heirarchy after penning a scathing review of the Cork Film Festival - which had given him the use of a free car ! - in which he stated that Irish culture would never move forward until it removed the stranglehold of the Church on the arts and free expression.

Haughey did have the grace to apologise for his reactionary colleagues, and promised that George would be welcome to return.

He was proud to be deported 10 years after Lenny Bruce, the only other American to be deported from Ireland.

"Nearly all the changes in which you're allowed to participate are in things which aren't very important. The real and difficult changes are those which give more and more people power to decide more and more things for themselves"- from The Little Red School Book

by Soren Hanson and Jesper Jenson |

|

Between 1972-4, George spent a lot of time in Greece - or more accurately, Sparta; renewing his links with his family and trying to sort out the land his father had left behind when he left for America.

In 1976 he returned to the US and bought a house in Philadelphia which he descibed as a 'beautiful city, largely black and very impoverished but with the best jazz radio station in the US at the time' (Temple University Jazz FM).

Back in the USA, George revived Zero briefly, devoting one issue to the communal group, MOVE, whose centre in Osage Avenue, Philadelphia, was fire-bombed from the air by the City police, resulting in the deaths of six adults and five children.

The group, who were mainly, but not exclusively black; were anti-materialist and not involved in violent insurrection; their crime was being an example of alternative living within the US ghettos, challenging the consumerist and apartheid principles of the American state. Although many connected with the movement are either dead or imprisoned, they still exist as a loose campaigning organisation, and have inspired activists from the US to Europe.

George financed the magazine with a grant from Renaud Bruce de Bourbon, brother of Phillipe de Bourbon, heir apparent to the extinct throne of France.(If you check the back cover it says 'Sponsored by the Poodle Club of Paraguay', where Renaud lived at the time.) It cost $3000 for 3000 copies, was printed by the same company who produce the National Geographic, and was distributed by members of the MOVE at the subsequent court hearings.

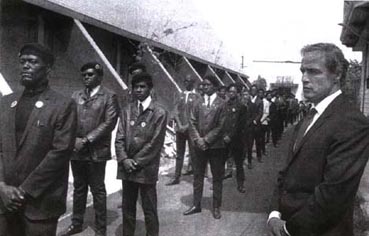

His contacts with the MOVE resulted in George being able to arrange the only filmed interview on Death Row with his friend Mumia Abu-Jamal, a journalist connected to the original Black Panthers, who was set-up in 1982 on a charge of murdering a policeman.

| * The Judge, Albert Sabo, sentenced more people to death than any other sitting judge in the US.

* The public defender didn't interview a single witness in preparation for the trial, and didn't have funds for defending a capital case.

* The prosecutor removed 11 qualified African Americans from the jury. He also argued for the death penalty because of Mumia's membership in the Black Panther Party, a practice later condemned as unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court.

* The racial bias of Philadelphia's courts has resulted in 120 people on death row, all but 13 non-white. |

|

|

| Marlon Brando at Little Bobby Hutton's funneral April, 1968. |

Despite appeals over the years by tens of thousands of people across the USA and Europe, including notables such as President Mitterand and the previous Pope; as well as mounting evidence over the years that Mumia was not guilty of the crime that he was convicted for, he remains in a cell after 25 years, his sentence commuted to life in 2001.

The film was taken around the campus circuit, and shown to students and activists to raise attention to Mumia’s case; and was later shown in Cuba, when George (and fiba) were invited to the Cuban Film Festival in 1998.

George also set up a citizens’ TV channel after moving to the first housing project in Philadelphia that took the idea of universal media access seriously, and had equipped the 500 apartments and buildings with cable TV and a small studio in the basement.

One of his most popular projects was a ‘reality TV’ soap about elderly citizens, the format later being lifted by CBS and turned into the popular serial ‘The Golden Girls’.

|

He moved back to London in 1986 from San Diego, but was almost immediately off on his travels again.

After driving through France and up to Spain, George retraced the journey he made as a youth, and contacting some of the people who had saved his life, which came to the notice of the French media.

He then spent 6 months in Tangiers from 1986-7, spending time with his old friend Paul Bowles. He has lived since then in South-East London, being an inspiration to new generations of artists and writers, throwing his energies into his film magazine fiba, which moved online in 1998.

He is currently looking for a publisher of his novel, Thermopylae, which he wrote many years after the war, but was the first writing which allowed him to confront the trauma which resulted from his experience. It is also a story about the timeless spirit of Sparta, of free individuals prepared to both defend the good in society and fight the bad, and of human struggle against fate and the fictions of history.

When many people would by now be looking back on such a restless life, and putting their feet up in the sun; George even now has a diary full of visitors, and sessions constructing the layers of articles on his websites. His vision of the world is modern - more so than many people generations younger who have not seen the span of the twentieth century that widely, that close, and emerged into the harsh light of the 21st; but, he is a true Spartan, one of the few that survived.

George Solomos at film studio The Mill, London, November 2002.

©John Heathcote 2007 |